Tarski's axioms

Tarski's axioms, due to Alfred Tarski, are an axiom set for the substantial fragment of Euclidean geometry, called "elementary," that is formulable in first-order logic with identity, and requiring no set theory (Tarski 1959). Other modern axiomizations of Euclidean geometry are those by Hilbert and George Birkhoff.

Contents |

Overview

Early in his career Tarski taught geometry and researched set theory. His coworker Steven Givant (1999) explained Tarski's take-off point:

- From Enriques, Tarski learned of the work of Mario Pieri, an Italian geometer who was strongly influenced by Peano. Tarski preferred Pieri's system [of his Point and Sphere memoir], where the logical structure and the complexity of the axioms were more transparent.

Givant's then says "with typical thoroughness" Tarski devised his system:

- What was different about Tarski's approach to geometry? First of all, the axiom system was much simpler than any of the axiom systems that existed up to that time. In fact the length of all of Tarski's axioms together is not much more than just one of Pieri's 24 axioms. It was the first system of Euclidean geometry that was simple enough for all axioms to be expressed in terms of the primitive notions only, without the help of defined notions. Of even greater importance, for the first time a clear distinction was made between full geometry and its elementary — that is, its first order — part.

Like other modern axiomatizations of Euclidean geometry, Tarski's employs a formal system consisting of symbol strings, called sentences, whose construction respects formal syntactical rules, and rules of proof that determine the allowed manipulations of the sentences. Unlike some other modern axiomatizations, such as Birkhoff's and Hilbert's, Tarski's axiomatization has no primitive objects other than points, so a variable or constant cannot refer to a line or an angle. Because points are the only primitive objects, and because Tarski's system is a first-order theory, it is not even possible to define lines as sets of points. The only primitive relations (predicates) are "betweenness" and "congruence" among points.

Tarski's axiomatization is shorter than its rivals, in a sense Tarski and Givant (1999) make explicit. It is more concise than Pieri's because Pieri had only two primitive notions while Tarski introduced three: point, betweenness, and congruence. Such economy of primitive and defined notions means that Tarski's system is not very convenient for doing Euclidian geometry. Rather, Tarski designed his system to facilitate its analysis via the tools of mathematical logic, i.e., to facilitate deriving its metamathematical properties. Tarski's system has the unusual property that all sentences can be written in universal-existential form, a special case of the prenex normal form. This form has all universal quantifiers preceding any existential quantifiers, so that all sentences can be recast in the form  This fact allowed Tarski to prove that Euclidean geometry is decidable: there exists an algorithm which can determine the truth or falsity of any sentence. Tarski's axiomatization is also complete. This does not contradict Gödel's first incompleteness theorem, because Tarski's theory lacks the expressive power needed to interpret Robinson arithmetic (Franzén 2005, pp. 25–26).

This fact allowed Tarski to prove that Euclidean geometry is decidable: there exists an algorithm which can determine the truth or falsity of any sentence. Tarski's axiomatization is also complete. This does not contradict Gödel's first incompleteness theorem, because Tarski's theory lacks the expressive power needed to interpret Robinson arithmetic (Franzén 2005, pp. 25–26).

The axioms

Alfred Tarski worked on the axiomatization and metamathematics of Euclidean geometry intermittently from 1926 until his 1983 death, with Tarski (1959) heralding his mature interest in the subject. The work of Tarski and his students on Euclidean geometry culminated in the monograph Schwabhäuser, Szmielew, and Tarski (1983), which set out the 10 axioms and one axiom schema shown below, the associated metamathematics, and a fair bit of the subject. Gupta (1965) made important contributions, and Tarski and Givant (1999) discuss the history.

Fundamental relations

These axioms are a more elegant version of a set Tarski devised in the 1920s as part of his investigation of the metamathematical properties of Euclidean plane geometry. This objective required reformulating that geometry as a first-order theory. Tarski did so by positing a universe of points, with lower case letters denoting variables ranging over that universe. Equality is provided by the underlying logic (see First-order logic#Equality and its axioms).[1] Tarski then posited two primitive relations:

- Betweeness, a triadic relation. The atomic sentence Bxyz denotes that y is "between" x and z, in other words, that y is a point on the line segment xz. (This relation is interpreted inclusively, so that Bxyz is trivially true whenever x=y or y=z).

- Congruence (or "equidistance"), a tetradic relation. The atomic sentence wx ≡ yz can be interpreted as wx is congruent to yz, in other words, that the length of the line segment wx is equal to the length of the line segment yz.

Betweenness captures the affine aspect of Euclidean geometry; congruence, its metric aspect. The background logic includes identity, a binary relation. The axioms invoke identity (or its negation) on five occasions.

The axioms below are grouped by the types of relation they invoke, then sorted, first by the number of existential quantifiers, then by the number of atomic sentences. The axioms should be read as universal closures; hence any free variables should be taken as tacitly universally quantified.

Congruence axioms

- Reflexivity of Congruence

The distance from x to y is the same as that from y to x. This axiom asserts a property very similar to symmetry for binary relations.

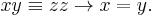

- Identity of Congruence

If xy is congruent with a segment that begins and ends at the same point, x and y are the same point. This is closely related to the notion of reflexivity for binary relations.

- Transitivity of Congruence

Two line segments both congruent to a third segment are congruent to each other; all three segments have the same length. This axiom asserts that congruence is Euclidean, in that it respects the first of Euclid's "common notions." Hence this axiom could have been named "Congruence is Euclidean." The transitivity of congruence is an easy consequence of this axiom and Reflexivity.

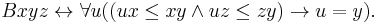

Betweenness axioms

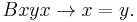

- Identity of Betweenness

The only point on the line segment  is

is  itself.

itself.

Draw line segments connecting any two vertices of a given triangle with the sides opposite the vertices. These two line segments must then intersect at some point inside the triangle.

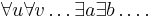

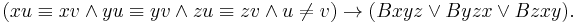

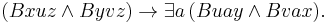

- Axiom schema of Continuity

Let φ(x) and ψ(y) be first-order formulae containing no free instances of either a or b. Let there also be no free instances of x in ψ(y) or of y in φ(x). Then all instances of the following schema are axioms:

Let r be a ray with endpoint a. Let the first order formulae φ and ψ define subsets X and Y of r, such that every point in Y is to the right of every point of X (with respect to a). Then there exists a point b in r lying between X and Y. This is essentially the Dedekind cut construction, carried out in a way that avoids quantification over sets.

- Lower Dimension

![\exists a \, \exists b\, \exists c\, [\neg Babc \and \neg Bbca \and \neg Bcab].](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/64609d1d3d15e01552416e433d58fab0.png)

In short, there exist three noncollinear points, and any model of these axioms must have dimension > 1.

Congruence and betweenness

- Upper Dimension

Three points equidistant from two distinct points form a line. Hence any model of these axioms must have dimension < 3.

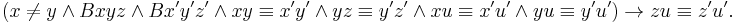

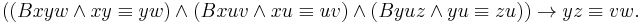

- Axiom of Euclid

Each of the three variants of this axiom, all equivalent over the remaining Tarski's axioms to Euclid's parallel postulate, has an advantage over the others:

- A dispenses with existential quantifiers;

- B has the fewest variables and atomic sentences;

- C requires but one primitive notion, betweenness. This variant is the usual one given in the literature.

- A:

Let a line segment join the midpoint of two sides of a given triangle. That line segment will be half as long as the third side. This is equivalent to the interior angles of any triangle summing to two right angles.

- B:

Given any triangle, there exists a circle that includes all of its vertices.

- C:

Given any angle and any point v in its interior, there exists a line segment including v, with an endpoint on each side of the angle.

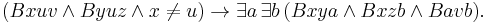

- Five Segment

Begin with two triangles, xuz and x'u'z'. Draw the line segments yu and y'u', connecting a vertex of each triangle to a point on the side opposite to the vertex. The result is two divided triangles, each made up of five segments. If four segments of one triangle are each congruent to a segment in the other triangle, then the fifth segments in both triangles must be congruent.

- Segment Construction

![\exists a\, [Bwxa \and xa \equiv yz].](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/60d62ed4dd34159eda885ad11f8234ca.png)

Given any two line segments, the second can be "extended" by a line segment congruent to the first.

Discussion

Starting from two primitive relations whose fields are a dense universe of points, Tarski built a geometry of line segments. According to Tarski and Givant (1999: 192-93), none of the above axioms is fundamentally new. The first four axioms establish some elementary properties of the two primitive relations. For instance, Reflexivity and Transitivity of Congruence establish that congruence is an equivalence relation over line segments. The Identity of Congruence and of Betweenness govern the trivial case when those relations are applied to nondistinct points. The theorem xy≡zz ↔ x=y ↔ Bxyx extends these Identity axioms.

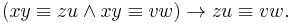

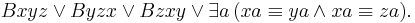

A number of other properties of Betweenness are derivable as theorems including:

- Reflexivity: Bxxy ;

- Symmetry: Bxyz → Bzyx ;

- Transitivity: (Bxyw ∧ Byzw) → Bxyz ;

- Connectivity: (Bxyw ∧ Bxzw) → (Bxyz ∨ Bxzy).

The last two properties totally order the points making up a line segment.

Upper and Lower Dimension together require that any model of these axioms have a specific finite dimensionality. Suitable changes in these axioms yield axiom sets for Euclidean geometry for dimensions 0, 1, and greater than 2 (Tarski and Givant 1999: Axioms 8(1), 8(n), 9(0), 9(1), 9(n) ). Note that solid geometry requires no new axioms, unlike the case with Hilbert's axioms. Moreover, Lower Dimension for n dimensions is simply the negation of Upper Dimension for n - 1 dimensions.

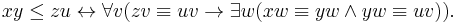

When dimension > 1, Betweenness can be defined in terms of congruence (Tarski and Givant, 1999). First define the relation "≤" (where  is interpreted "the length of line segment

is interpreted "the length of line segment  is less than or equal to the length of line segment

is less than or equal to the length of line segment  "):

"):

In the case of two dimensions, the intuition is as follows: For any line segment xy, consider the possible range of lengths of xv, where v is any point on the perpendicular bisector of xy. It is apparent that while there is no upper bound to the length of xv, there is a lower bound, which occurs when v is the midpoint of xy. So if xy is shorter than or equal to zu, then the range of possible lengths of xv will be a superset of the range of possible lengths of zw, where w is any point on the perpendicular bisector of zu.

Betweenness can than be defined as

The Axiom Schema of Continuity assures that the ordering of points on a line is complete (with respect to first-order definable properties). The Axioms of Pasch and Euclid are well known. Remarkably, Euclidean geometry requires just the following further axioms:

- Segment Construction. This axiom makes measurement and the Cartesian coordinate system possible—simply assign the value of 1 to some arbitrary line segment;

Let wff stand for a well-formed formula (or syntactically correct formula) of elementary geometry. Tarski and Givant (1999: 175) proved that elementary geometry is:

- Consistent: There is no wff such that it and its negation are both theorems;

- Complete: Every sentence or its negation is a theorem provable from the axioms;

- Decidable: There exists an algorithm that assigns a truth value to every sentence. This follows from Tarski's:

- Decision procedure for the real closed field, which he found by quantifier elimination;

- Axioms admitting of a (multi-dimensional) faithful interpretation as a real closed field.

Gupta (1965) proved the above axioms independent, Pasch and Reflexivity of Congruence excepted.

Negating the Axiom of Euclid yields hyperbolic geometry, while eliminating it outright yields absolute geometry. Full (as opposed to elementary) Euclidean geometry requires giving up a first order axiomatization: replace φ(x) and ψ(y) in the axiom schema of Continuity with x ∈ A and y ∈ B, where A and B are universally quantified variables ranging over sets of points.

Comparison with Hilbert

Hilbert's axioms for plane geometry number 16, and include Transitivity of Congruence and a variant of the Axiom of Pasch. The only notion from intuitive geometry invoked in the remarks to Tarski's axioms is triangle. (Versions B and C of the Axiom of Euclid refer to '"circle" and "angle," respectively.) Hilbert's axioms also require "ray," "angle," and the notion of a triangle "including" an angle. In addition to betweenness and congruence, Hilbert's axioms require a primitive binary relation "on," linking a point and a line. The Axiom schema of Continuity plays a role similar to Hilbert's two axioms of Continuity. This schema is indispensable; Euclidean geometry in Tarski's (or equivalent) language cannot be finitely axiomatized as a first-order theory. Hilbert's axioms do not constitute a first-order theory because his continuity axioms require second-order logic.

Notes

- ^ Tarski and Givant, 1999, page 177

References

- Franzén, Torkel (2005), Godel's Theorem: An Incomplete Guide to Its Use and Abuse, A K Peters, ISBN 1568812388

- Givant, Steven (1999) "Unifying threads in Alfred Tarski's Work", Mathematical Intelligencer 21:47–58.

- Gupta, H. N. (1965) Contributions to the Axiomatic Foundations of Geometry. Ph.D. thesis, University of California-Berkeley.

- Tarski, Alfred (1959), "What is elementary geometry?", in Leon Henkin, Patrick Suppes and Alfred Tarski, The axiomatic method. With special reference to geometry and physics. Proceedings of an International Symposium held at the Univ. of Calif., Berkeley, Dec. 26, 1957-Jan. 4, 1958, Studies in Logic and the Foundations of Mathematics, Amsterdam: North-Holland, pp. 16–29, MR0106185. Available as a 2007 reprint, Brouwer Press, ISBN 1-443-72812-8

- Tarski, Alfred; Givant, Steven (1999), "Tarski's system of geometry", The Bulletin of Symbolic Logic 5 (2): 175–214, doi:10.2307/421089, ISSN 1079-8986, JSTOR 421089, MR1791303, http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/summary?doi=10.1.1.27.9012

- Schwabhäuser, W., Szmielew, W., and Alfred Tarski, 1983. Metamathematische Methoden in der Geometrie. Springer-Verlag.

- Szczerba, L. W., 1986, "Tarski and Geometry," Journal of Symbolic Logic 51: 907-12.

![\exists a \,\forall x\, \forall y\,[(\phi(x) \and \psi(y)) \rightarrow Baxy] \rightarrow \exists b\, \forall x\, \forall y\,[(\phi(x) \and \psi(y)) \rightarrow Bxby].](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/da299cc114a866e821796ad12c1502dd.png)